Walking to Law: The Unmapped Journey of Manimaran

If no path exists, create one!

On the outskirts of Ulundurpet, in a quiet village called Thirupeyar in Kallakurichi district, Tamil Nadu, a young man once travelled twelve kilometres for a newspaper. Not for leisure, Not out of routine, but because that newspaper was his classroom, his mentor, and his bridge to a future he could barely afford to imagine.

That young man was Manimaran, today an Assistant Professor of Law. His journey to the legal profession was neither linear nor privileged; it was shaped by migration, material scarcity, moral discomfort, and an unyielding engagement with questions of justice.

One such essay reached a reader who paused. A relative, freshly graduated from law school, recognised something familiar in Manimaran’s writing. "This isn’t disinterest", he said. This is the direction. Law, he suggested, might be where Manimaran truly belonged. The suggestion refused to leave. When Manimaran finally explored law seriously, reality arrived without hesitation. His academic record shut the doors of government law colleges. There was only one opening left but with a lift, the Common Law Admission Test. Which is Risky, Competitive, Uncertain. Still, he chose it. Against expectation and uncertainty, Manimaran decided to pause everything else, take a year off, and prepare for CLAT, placing his future on a single examination, and his faith in himself.

A Year of Solitude and Newspapers

Preparation for CLAT required distance from pressure, expectation, and immediate survival. Delhi could not offer that. He returned to his family’s native village in Tamil Nadu. The house there was used as a storage space for agricultural produce. It had no academic infrastructure, but it offered what he needed most, freedom from pressure. Each day, he travelled twelve kilometres to the nearest town to buy a newspaper. The journey drained time and energy - overcrowded buses, long waits, and nowhere to sit. Eventually, he found a workaround: paying in advance and collecting newspapers weekly on Sundays.The newspaper became his syllabus. He read it slowly, deliberately. Underlining unfamiliar words, writing their meanings, tracking political and judicial developments through clippings, and reading aloud to improve pronunciation. A single preparatory book supplemented this routine. When the CLAT results were declared, Manimaran did not qualify.

Last name on the list that changed everything

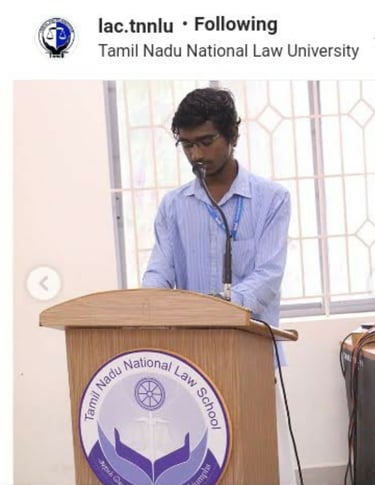

Disappointed but undeterred, he returned to Delhi. Shortly thereafter, Tamil Nadu National Law University (TNNLU) announced direct admissions to fill vacant seats. Manimaran applied, without expectation, His name appeared but Last on the list. Once again, he returned to Tamil Nadu, this time as a law student.

Learning amid unease

TNNLU offered what had long been missing: regular meals, a library, computers, and structured learning. Yet Manimaran struggled to feel at ease.After years of searching for a place to study, the abundance felt morally unsettling. The contrast between those who had access and those who did not stayed with him, uncomfortably. Delays in scholarship deepened this unease. As a first-generation graduate, arranging substantial fees upfront was not just difficult, it was nearly impossible. The institutional apathy, especially from a public institution meant to promote inclusion, sharpened his discontent. Academically, too, something felt distant. Legal education appeared formal, procedural. Removed from the realities he had hoped to address. Looking back, he describes this phase as one of closure - not entirely wrong, but incomplete. Critique without belief in change had its limits.

Holding On: Discipline, Nature, and Friendship

Caught between obligation and disillusionment, Manimaran leaned into discipline. The university library became his constant companion, opening at 6 a.m. and closing at 10 p.m. His days followed a rigid routine, driven by a constant need to justify the opportunity he had received. What saved him from the collapse were three pillars. Nature - in morning and evening walks, trees lining his path, sunrises and sunsets met with yoga and meditation, Health - simple food, timely meals, restraint and the presence of his three close friends - Anto Robert, Richis Jesvanth, and Rithik Sushil. They stayed, even when his insistence on questioning practices, advocating silence in the library, spending on campus events, administrative accountability, made things uncomfortable. They argued, disagreed, and reflected. But never dismissed.

From Resistance to Responsibility

Gradually, something shifted.Scholarship issues were resolved through government clarifications and persistent representations. He gradually moved from rejection to dialogue. Research writing became central to his academic life, offering a way to engage meaningfully with societal issues. Conferences and seminars provided platforms to articulate his concerns. Activism followed, not as protest alone, but through formal mechanisms such as grievance portals, written representations, and RTI applications. What began as frustration transformed into agency.

Where it all began

Manimaran’s outlook is inseparable from his childhood. His parents migrated from Tamil Nadu to Delhi in the early 1990s, working as a domestic worker and car cleaner. Long working hours left little room for social life. Home was quiet. Survival came first. He studied at a Delhi Tamil Education Association school, where subsidised education and midday meals sustained many migrant children. A newspaper subscribed to by a relative became his first doorway into the world.

Law, Not as escape - But as commitment

Today, Manimaran’s journey has taken him from a Tamil aided school to the National Law School of India University (NLSIU), and into academia as an Assistant Professor of Law. Yet, he resists narratives of personal triumph. For him, law was never about status. It was about refusing complacency. About responding, not turning away from the injustices that shaped his life.

Once, he travelled twelve kilometres for a newspaper.Now, he teaches law to those who will shape institutions. Not because the path was laid out, but because he chose, again and again, to walk it.

The expected path didn’t fit!

Like many students from working class families, Manimaran grew up with a future already decided for him. Engineering was Practical, Safe, Respectable.But classrooms have a way of revealing truths early. His grades slipped, his interest faded, and his attention kept drifting. Not to machines or formulas, but towards people, power, and the quiet inequalities that shape everyday life. He found himself writing essays about social issues. He questioned systems. He observed closely.

Manimaran – The Man of Perseverance and Responsibility

Reach out to Manimaran at manimaran.r8800@gmail.com